There’s a common quote (often falsely attributed to Mark Twain) that goes something like “A lie can make it halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on”. And in these days of social media where a tweet or Facebook post can “go viral” in mere minutes, it’s easy to be misled.

Even the BBC sometimes includes a joke news item on April Fools Day. From a spaghetti harvest in Switzerland back in 1957 to a new species of penguin that could fly in 2008, they’ve broadcast a few joke stories over the years. And if I hadn’t checked the date that day, I might even fall for it (especially if it’s early and I haven’t had my first cup of coffee yet – ahem…). So how do I stop myself from being hoodwinked?

Step Number 1: Check the source

The first thing to do is to look at where the article/post/link or whatever has come from. Is it a reputable news website, like the BBC or Reuters? Is it from a national newspaper?

There are a few satirical and just plain fake news sites out there that you should know about – I’ve put a list of known offenders at the bottom of this article. If you aren’t sure that it’s authentic, try Googling the name of the website and looking for an “about us” section – joke websites often include something there to show that they aren’t taking themselves too seriously.

I’d also be careful with articles from tabloid newspapers or gossip magazines – although I wouldn’t go as far as calling them fake news, they often use “clickbait” headlines that are hugely exaggerated to try to grab your attention, but when you actually read the article you discover that the answer to the headline “Are giant flesh-eating robots taking over the world?” is a simple “No.” And typically the ‘unnamed source close to the celebrity’ is actually code for “what my Aunt Hilda said at the hairdressers” rather than an actual quote from a relevant person.

Step Number 2: If it doesn’t have a reliable source, be wary

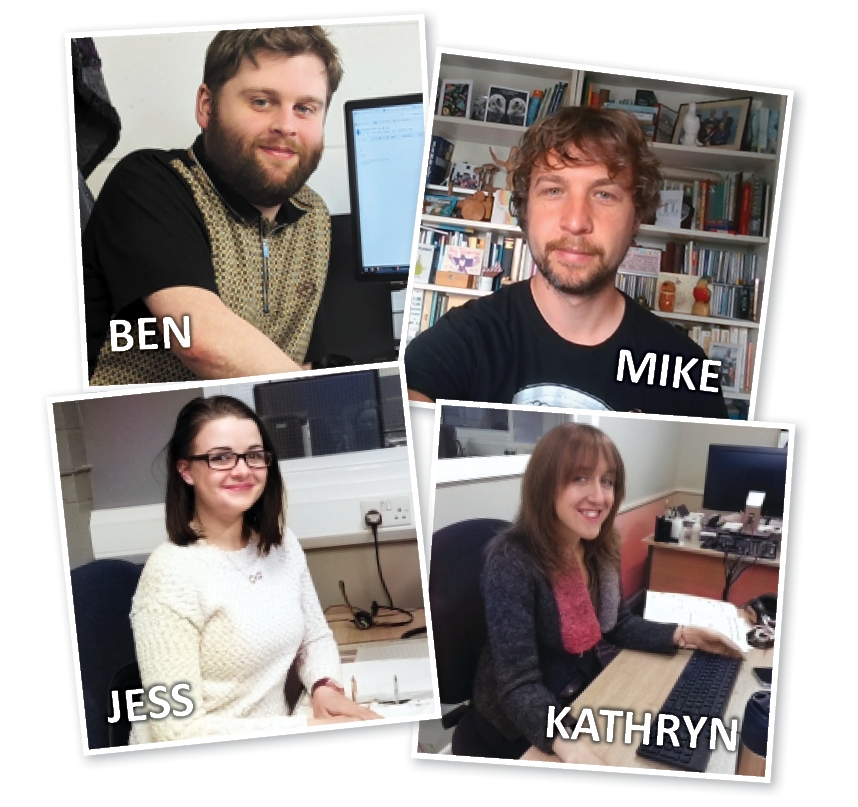

Twitter is a common culprit for opinions being stated as facts – so it’s a good idea to take things you see on there with a pinch of salt. If you suspect someone’s talking nonsense, you might want to check their profile to see if they know what they’re talking about. Most people include their profession in their Twitter bio – I’ll use the astronaut Tim Peake as an example:

Under his name and Twitter handle (the bit with an @ in front of it) it clearly states that he’s an astronaut who spent 6 months in space – so you can probably trust his word on subjects like space and astrophysics. There’s also a little blue tick next to his name – that means he’s been ‘verified’ by Twitter as the real deal, rather than someone pretending to be him. Facebook also uses this little blue tick to confirm famous people’s pages.

Look carefully at memes and chain posts

One thing that’s very common on social media these days is memes (photos with text over the top).

Usually memes are designed to be funny – but unfortunately, sometimes the people who make these memes have a bit of an agenda to push. If you see a photograph with a lot of angry text over the top of it, without any link or source to back up what the text is saying, chances are it’s a fake post designed to make people angry at certain groups of society.

One of these fake image posts that keeps doing the rounds is two photos of the House of Commons on different days – the first one shows the room full of MPs, the second one shows it practically empty. Here’s an example of the type of thing I mean:

The text underneath the images changes according to the political issue of the moment, but it’s usually something like “MPs voting for an increase in their salaries” over the picture of the crowded room, and “MPs voting on a national living wage/homelessness/NHS reform” over the empty room picture. However, there’s rarely a reliable source to back up the claims made by the text. In fact, the crowded room picture is of MPs gathering after the 2010 general election, and the empty room picture is from a late night debate – so it’s not surprising that there’ll be different numbers of MPs present. The trouble is, anyone could easily pop a bit of text over the top of the picture to say whatever they like.

Another common thing with Facebook is chain text posts that tell people to “Share this to show your support for X”, or “I bet only my REAL friends will share this”, or “Copy and paste this, don’t share it, to prove that you’ve actually read it”. They’re designed to goad you into sharing the post by implying that if you don’t share it, you’re a bad person (you’re not) or you don’t care about the cause they’re supporting. Generally these posts are harmless – nothing bad will happen to you if you do share them, but a lot of people find them quite annoying.

But there’s also been an increase in recent times of “advice” chain posts that just aren’t true, but that people are encouraged to share to try and help others. Every few years there’s one about how “Facebook is going to steal your photos, repost this bit of legal-sounding nonsense to stop them” – but it isn’t true, you can just ignore it.

This happens a lot in uncertain times, too. For example, there is absolutely no evidence that drinking hot liquids or gargling with antiseptics will stop you catching coronavirus. But many people have shared a text from “a friend of a friend who works for the NHS” that says just that.

I completely understand why people would want to share this – we all want to do our bit and help each other. But beware of conveniently vague sources giving advice that hasn’t been approved by the government or the World Health Organisation.

Now I don’t want to scare anyone off from using social media or sharing news articles that you find interesting – it’s a great way to start a discussion with your friends. Just a gentle reminder to take the things you read online with a pinch of salt.

Spoof or fake news websites:

https://www.thedailymash.co.uk/

https://southendnewsnetwork.net/